Dyslexia

Learning Disability - Dyslexia

- The highly verbal five-year-old who can’t master the alphabet.

- The bright, creative seven-year-old who has not grasped reading.

- The teenager whose mediocre grades are blamed on “lack of motivation”.

- The college student who scraped by in high school and now finds herself in over her head.

What these otherwise bright, sociable young people have in common is a disability which makes learning in the “usual” way difficult.

Our educational system relies mainly on reading and writing to convey information and measure achievement, so dyslexics struggle in the system. Before the invention of written language, dyslexia didn’t exist. People with the gift of dyslexia were probably the custodians of oral history because of their excellent ability to memorise and transmit the spoken word.

Dyslexia can be viewed as a different kind of mental process. Very often it is a gifted mind, but it is a mind that is physiologically different. This is not a defect in the true sense, but a difference in the way information is processed by a brain that is, for all intents and purposes, normal. Difficulties understanding the basic correspondence between symbols (such as letters) and their sounds lead to subtle miscues in the organisation of cognitive systems in the brain of the Dyslexic. These miscues are present at birth and are influenced to some degree by heredity.

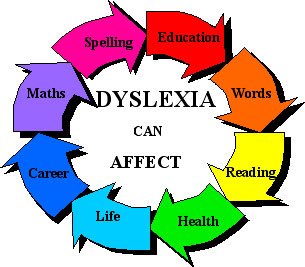

Thus Dyslexia is “a developmental disorder marked by difficulty in learning to read, write, and do math despite adequate intelligence, conventional instruction, and socio-cultural opportunity.” This means, a dyslexic is a person who has a normal or above average IQ but is severely below their expected reading, writing, and/or math level based upon their overall intelligence. This person has received a normal education yet still falls below expectation.

The manifestations of dyslexia are two-fold. On one hand a child with a dyslexic mind will have trouble from the very beginning learning to understand speech and make himself understood. Because his mind cannot easily recall words, the dyslexic child may have to describe what he wants. E.g the child may say “I want that thing we use to write with…” instead of asking for a pencil. The mind of a dyslexic child will often have trouble sequencing, so the words will get twisted — “basgetti, mellow, aminals” or spoken in the wrong order, “please up hurry!”

When a child enters school he may struggle with the positioning of letters that distinguishes a “p” from a “d” from a “b.” “Was” becomes “saw,” “pet” can be read as “bet.” Even in upper grades, the dyslexic mind may read “nuclear” as “unclear.” What makes dyslexia difficult to recognise is that many of its characteristics are a natural part of the maturing process of young children. It is when a child gets “stuck” in these stages and they last longer than normal, that parents and teachers need to recognise a potential difficulty.

Often the child appears to be lazy, not trying hard enough, or just slow. In fact, the dyslexic child’s mind is working harder to fill in the gaps between what he actually sees, hears and feels in the outer world, and how he thinks about these things in his head and puts them into words. The dyslexic mind needs more help in sorting, recognising, and organising the raw materials of language for reading and spelling. Some “red flag” behaviours that may indicate that a dyslexic mind is at work are:

- Avoiding difficult tasks, especially if they involve reading, writing or spelling.

- Spending an inordinate amount of time on tasks or not finishing assignments.

- Propping his head up when writing.

- Guessing when she doesn’t know a word.

- Knowing a word one day but forgetting it the next.

- Mixing cursive with manuscript letters.

- Having a vocabulary which exceeds his reading ability.

- Understanding math conceptually, but having difficulty reading and writing problems.

- Having a wide spread between performance and verbal scores on standardised tests.

- Acting inappropriately or demanding excessive attention.

On the other hand the dyslexic mind may have tremendous creative ability that allows a child to sing or play an instrument easily or at an early age. The child with a dyslexic mind may be able to build whole cities with tiny interlocking blocks and no directions, or solve three-dimensional puzzles without difficulty. Many of our most gifted athletes have dyslexic minds that can “see” the entire field of play and the relative position of all the players simultaneously.

Common identifiers of dyslexia include, but are not limited to:- Family history of reading problems;

- no enjoyment of reading as a leisure activity;

- Specific problems in reading that include

- pronouncing new words,

- difficulty distinguishing similarities and differences in words (no for on), and

- difficulty discriminating differences in letter sound (pin, pen)

- reversal of words and letters,

- disorganisation of word order,

- poor reading comprehension, and

- difficulty applying what has been read to social or learning situations.

- problems of spelling, and grammar

- developmental history of problems in coordination and left/right determination

- poor visual memory for language symobols;

- auditory language difficulties in word finding, fluency, meaning, or sequence;

- difficulty transferring information from what is heard to what is seen and vice versa in a child with an average or above average IQ

Because they are visual thinkers, dyslexics are often confused by letters, symbols and written words. Often, their minds do not even perceive the print on the page accurately or consistently. As they do not “see” the letters and words correctly, they experience frustration when they try to learn to read and write.

Common Misconceptions

- Dyslexic children are not “retarded”. Given the right opportunity and proper special education, they can develop into “normal” adults.

- Dyslexics do not have a behavioural disorder. However, if no corrective action is taken they can develop low self esteem leading to Behavioural problems

- There is no scientific evidence that Dyslexic children will benefit with medicines or “tonics”.

- Dyslexics can become successful adults with the right opportunities

- Dyslexic individuals do not have greater incidence of eye problems than do individuals with normal reading ability.

- There is no scientific evidence that visual training (including eye muscle exercises, ocular tracking or pursuit exercises, or glasses with bifocals or prisms) leads to significant improvement in the performance of dyslexic individuals.

- Dyslexic individuals do not have greater incidence of hearing problems than do individuals with normal reading ability.

- There is no scientific evidence that speech training leads to significant improvement in the performance of dyslexic individuals.

Dyslexia is not a disease. It is a disability like clubfoot. The dyslexic mind is a physiological deviation from normal, like albinism. Like any physical disability, a child with dyslexia can, however, be taught to cope using appropriate teaching methods, and to compensate by using strengths to overcome weaknesses. Doctor Samuel T. Orton and his associates and successors pioneered the most appropriate teaching approach for the dyslexic mind. It has proven to be both scientifically sound and practically effective. The essentials of this instructional approach include:

- using all the pathways to the brain—sight, sound, touch and movement,

- teaching the alphabetic-phonic system on which our language is based;

- using sounds of letters for both reading and spelling;

- explaining rules for dividing words into syllables and how different kinds of syllables affect vowel sounds;

- presenting information in a sequential manner that progresses from the simple to more complex, moving the student through the material step-by-step; and

- building on success.

However, If undiagnosed or improperly addressed, dyslexia can produce years of frustration for affected children. Dyslexia can make a child feel “stupid” because the child sees contemporaries reading and working with numbers, and he can’t keep up. Because it relies more on language skills than these other gifts, school very quickly becomes a nightmare of frustration for a dyslexic child. Because a dyslexic mind cannot learn whole words by sight, a dyslexic child has trouble learning to read by traditional methods. Organising his desk or homework assignments or holding a pencil correctly will be hard work. The child sees his peers succeeding while he is failing. Because he is bright, he knows something is wrong. If parents and teachers fail to recognise and respond to his struggle, he becomes afraid. This fear can cause him to act out inappropriately. The student encounters failure every day in school and his self-esteem takes a beating.

Thus the importance of identifying a learning disability as soon as possible, so the child can begin to learn in alternative ways and achieve success in school, cannot be emphasised enough. If not detected and treated early, they can have a tragic “snowballing” effect. For instance, a child who does not learn addition in elementary school cannot understand algebra in high school. The child, trying very hard to learn, becomes more and more frustrated, and develops emotional problems such as low self-esteem in the face of repeated failure. Some learning disabled children misbehave in school because they would rather be seen as “bad” than “stupid”.

By the time the dyslexic becomes an adult, the inability to read and write well is a shameful secret. The person is convinced that it is a sign not only of ignorance, but unworthiness. This unfortunate self-perception can make adult dyslexics secretive and hostile.

Current teaching methods are not effective for many of our most talented children. Mistakenly labelled “slow,” “inattentive,” or lazy, they lose self-esteem in the early school years, and may become rebels. Many adult dyslexics succeed in life despite being functionally illiterate. Often, they invent elaborate subterfuges to hide their “shameful” secret.

The cornerstone of management is remedial (“special”) education. This should ideally begin early, when the child is in primary school.Using specific teaching strategies and teaching materials, an Individualized Educational Program must be tailor made to reduce or eliminate the child’s deficiencies in specific learning areas identified during the child’s educational assessment.Remedial sessions are necessary twice- or thrice-weekly for a few years to achieve academic competence.However, even after adequate remedial education, subtle deficiencies in reading, writing and mathematical abilities still persist.